Conflicts occur for many reasons and involve diverse actors. Considering the effects that civilians are facing, especially women and children, they need to be included to peace process to determine their own society’ future. In this blog post, the importance of power sharing and inclusion of women to peace and conflict process will be discussed. Peace processes that include women are more successful and sustainable (DPI, 2019).

UNSCR 1325 and Its Principles

In order to bring gender perspective to peace processes, the UN Security Council adopted 1325 article at its 4213th meeting on 31 October 2000. This focused on civilians, particularly women and children, who make up the majority of those who suffer as a result of armed conflict.

UNSC Resolution 1325 recognizes that through an understanding of the impact of armed conflict on women and girls, effective institutional arrangements to guarantee their protection and full participation in the peace process can significantly contribute to the maintenance and promotion of international peace and security.

It expresses Security Council willingness to incorporate a gender perspective into peacekeeping operations, and urges the Secretary-General to ensure that, where appropriate, field operations include a gender component.

The UNSCR 1325 article guides the word and spirit of importance of the effective gender inclusion to peace.

Gender perspective in peace process involves making gender equality issues transparent and comprehensible to the public. It also necessitates analysis of policies and practices with a view to take necessary actions for change, as stated by the UN.

Participation of Women to Peace and Conflict Processes

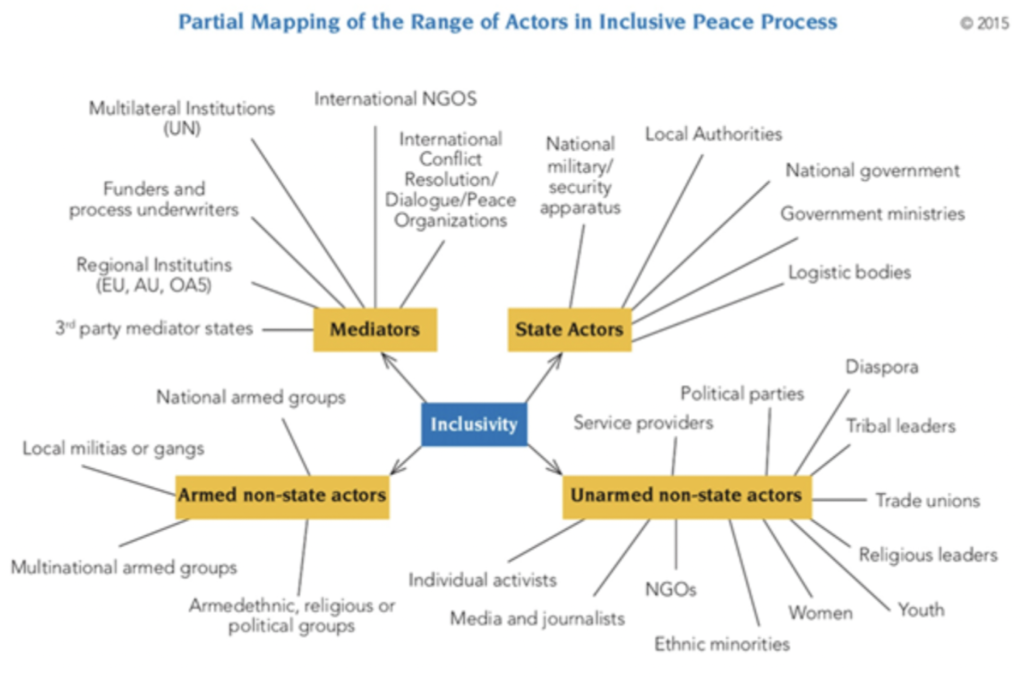

Peacebuilding involves the rebuilding of institutions within a country to create conditions for lasting peace. As experts points out, peacebuilding is the process of creating self-supporting structures that “remove causes of wars and offer alternatives to war in situations where wars might occur.” (Galtung, 2002). The academics insist that peace agreements signed between leaders and/or elites are not enough to secure long-term, sustainable peace. Long-term peace requires trust, which can be built by participation and attendance of other actors. An inclusive peace should contain mediators, state actors, armed non-state actors and unarmed non-state actors (Anderlini, 2021).

The UNSCR 1325 article guides the word and spirit of importance of the effective gender inclusion to peace.

Gender perspective in peace process involves making gender equality issues transparent and comprehensible to the public. It also necessitates analysis of policies and practices with a view to take necessary actions for change, as stated by the UN.

According to research, during conflicts, women are more likely to viewed as victim or survivor, rather than active participants in legal affairs, politics and governance as many studies indicate. To overcome this, International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN) underlines some means through which women can participate in the peacebuilding process:

- Running to the Problem and Taking on the Responsibility to Protect

- Stopping the Cycle of Pain, Giving Meaning to Loss

- Consultation, Trust, & Responsibility to Represent

- Tackling Discrimination and Asserting the Universality of Human Rights

It is known that conflict and peace processes provide the opportunities to re-build the whole existing system. Women peacebuilders can bring the problems that community has into the peace table and insist the solutions for long-term, permanent peace. Women are actors within society who can voice issues and concerns.

Opportunities & Experiences: Current Situation of Women Inclusion in Peace Processes

It has been 21 years since UNSCR 1325 article was released and it is obvious that women visibility on peace & conflict processes has been increased. This is a very positive change, yet it does not necessarily mean that women are given enough opportunities to participate in negotiations and important decisions about their lives. In some cases, the presence of women at the table is merely symbolic.

ICAN lists some of the barriers to women:

- Mediator does not consider inclusion/engagement of women a priority

- The Parties Resist Women’s Inclusion

- “Who are they?” The legitimacy of women’s civil society groups is questioned

- “The Process is delicate – we can’t overload it “

- “The talks are about ‘technical’ military/security issues. Women/civil society can join later”

- Exclusion of women is cultural. The Peace table isn’t the place to deal with ‘women’s issues’ or gender equality

Women’s participation in the negotiations is fundamental. Representation must go beyond symbolic form, as it needs to be practiced effectively to have progress.

Conclusion

As stated by DPI, feelings of pain, suffering, fear, loss, hate, despair, anger and sadness experienced during conflict are common to men and women. However, researches indicate that women are more willing and capable of moving beyond these feelings of pain and hate and are more adept at looking forward to create a new and safe future for their families and society. Many recent studies show that all around the world, conflict resolution processes which include women have a lower rate of deadlocks.

On the other hand, given their presence in the practice and advocacy around peace via UNSCR 1325, it would seem obvious that women peacebuilders should be a well-represented and recognized cohort in the mainstream peace and mediation community by now. But it is an unfortunate fact that they mostly remain overlooked, excluded, and largely unacknowledged in considerable cases.

About the Author:

Zübeyde Karagöz is a Junior Officer with Trust’s TPM and Research Department. She completed her MA at Istanbul Bilgi University, and works in humanitarian sector, where she focuses on peace building, gender and journalism.

References:

Democratic Progress Institute, 8 Years of Democratic Progress Institute In Photographs, p.24, 2019.

Democratic Progress Institute, https://www.democraticprogress.org/

Galtung, Johan (2002). Searching for Peace: The Road to TRANSCEND. Pluto Press.

Macharia, Sarah (2016). Gendered Narratives, On Peace, Security and News Media Accountability to Women. In Berit von der Lippe& Rune Ottosen (eds.), Gendering War and Peace Reporting. Nordicom: Goteborg.

International Civil Society Action Network, https://icanpeacework.org

Orgeret, Skare Kristen (2016). Conflict and Post-Conflict Journalism Worldwide Perspectives. In Kristin Skare Orgeret& William Tayeebwa (eds.), Journalism in Conflict and Post-Conflict Conditions Worldwide Perspectives. Nordicom: Goteborg.

Orgeret, Skare Kristin (2016). Women Making News. Conflict and Post-Conflict in the Field. In Kristin Skare Orgeret& William Tayeebwa (eds.), Journalism in Conflict and Post-Conflict Conditions Worldwide Perspectives. Nordicom: Goteborg.

Swaine, Aisling (2017). Furthering Comprehensive Approaches to Victims/Survivors of Conflict-related Sexual Violence: An Analysis of National Action Plans on Women, Peace and Security in Indonesia, Nepal, Philippines, and Timor Laste, UN Women.

United Nations Educational, Scientific and and Cultural Organization (2012). Gender-Sensitive Indicators for Media: Framework of Indicators To Gauge Gender Sensitivity in Operations and Content. France: Paris.

United Nations Security Council Resolution, Resolution 1325 (2000), http://unscr.com/en/resolutions/doc/1325.

Sanam Naraghi Anderlini, MBE, “Guaranteeing Women Peacebuilders Are at Peace Tables”, International Civil Society Action Network (ICAN), 2021, (Presentation) London.