Ten months after the outbreak and rapid spread of the novel Coronavirus most people worldwide have been affected by the pandemic and their daily lives disrupted. The Middle East was hit relatively early on by the virus, but due to a variety of different approaches taken by countries in the region, infection numbers and policy restrictions vary greatly between states. While COVID-19 brought economic downturn and a health crisis for countries worldwide, for those states affected by conflict and economic turmoil, the virus is aggravating already dire circumstances. Some population groups, however, are especially vulnerable to the economic, social, and health impacts of the global pandemic.

Since the outbreak of COVID-19, over 90,000 travel restrictions were implemented worldwide, leaving migrants and refugees stranded and cut off from their families, with their employment in jeopardy and residence permits expired. The UN categorizes the challenges migrants are facing due to COVID-19 in three interlocking crises: a health crisis, a socio-economic crisis, and a protection crisis.

The spread of COVID-19 in the Middle East

As of the beginning of October 2020, the WHO records over 2.5 million COVID-19 infections in the Middle East, with cases still rising in most countries. Especially the small states of the Gulf register a high rate of infections per one million inhabitants, notably Qatar with 44,144 and Bahrain with 43,449. Israel is grappling with another surge of infections, with the highest number of new cases in the last 24 hours at the time of writing. Similarly, Iran and Iraq are struggling to contain the spread of the virus, with infection numbers increasing rapidly. Iran furthermore registers a high fatality rate due to COVID-19, which is only exceeded by Egypt and most worryingly, Yemen. In the war-torn country, 29% of all confirmed infections are fatal. While it is to be assumed that in some countries of the region many cases go undetected due to low testing capacities or for political reasons, the contrast to the low fatality rate in the Gulf states highlights the dire situation and the stark differences in health care provision within the region.

Migration in the Middle East

The Middle East has always been shaped by migration, being simultaneously a point of origin, transit route, and destination for migrants and refugees alike. Accordingly, migration patterns vary greatly between countries and contexts. While the Gulf states record some of the largest figures of temporary labor migration in the world, other countries in the Middle East are facing largescale internal displacement and an exodus from their territory due to conflict and economic hardship. Reasons to migrate from, within or to the region are manifold and are influenced by a variety of personal, cultural and socio-economic factors. Most commonly, driving factors include high unemployment, especially amongst youth, low salaries, conflict, economic hardship, and the hope for a better future abroad.

However, the influx of migrants to the region is considerably higher than the emigration rate, with migration often remaining intraregional. In 2019 over 16.5 million persons migrated from one country in the region to another, with Turkey, Jordan and Saudi Arabia being the most frequent destinations. Additionally, the Middle East became home to over 31 million persons from outside the region in 2019, of whom most originated from South and Southeast Asia. In the same year, approximately 10 million people left the Middle East to migrate to a variety of different countries and regions, most commonly North America and Western Europe.

Since the high demand for labor force, especially in construction and domestic work in the Gulf states, create many job opportunities with comparatively higher wages, many workers from Africa, Asia and the Middle East decide to temporarily work abroad. This is in turn, means that labor migrants are a corner stone of the economy of many states. According to UN ESCWA about 40% of workers in Arab states are migrant workers, constituting the highest share worldwide. Temporary labor migration is often managed through the so-called kafala or sponsorship system, which is predominant in the Gulf states, Lebanon and Jordan. The system, however, has been frequently criticized for making migrant workers dependent of their sponsor.

The region is furthermore hosting the largest number of refugees worldwide, with 5.5 million Syrians alone finding refuge in neighboring countries. Moreover, the Middle East has witnessed largescale internal displacement in recent years, with 11.5 million persons being displaced within their country in Syria, Iraq and Yemen alone.

Migration in the time of COVID-19

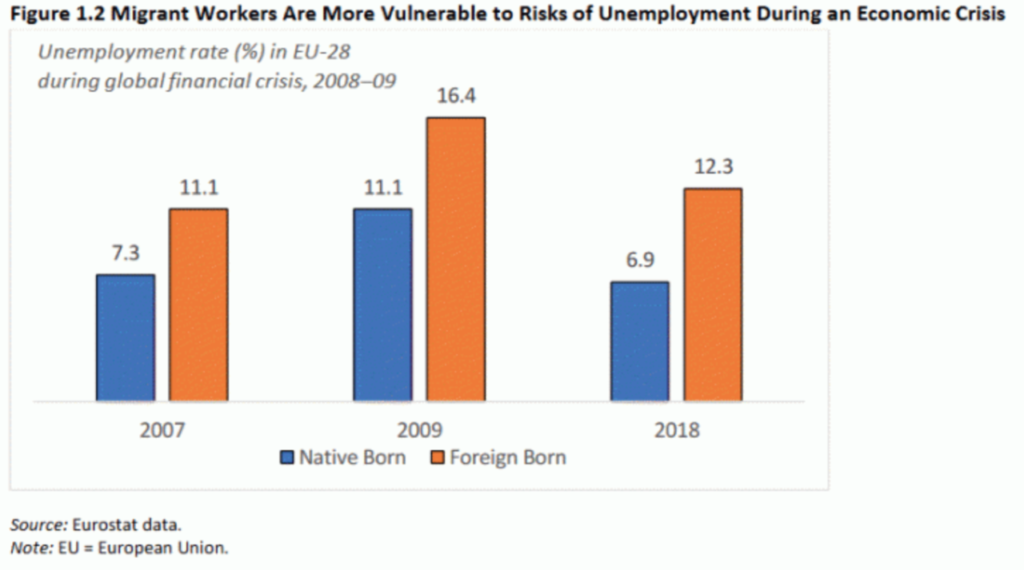

Refugees and internally displaced persons are particularly vulnerable to COVID-19 and at a high risk of infection. Especially in camp settings, living conditions are poor, social distancing is often impossible and access to water, sanitation and health services is limited. With nearly 7 million officially registered refugees and a considerably high number of unregistered refugees this poses a challenge for many countries in the Middle East. Unregistered refugees might also shy away from accessing medical services in case of an infection out of fear of being deported. Often working in the informal sector, refugees and internally displaced are dependent on a daily income which stopped due to lockdowns and economic downturn.

Similarly, temporary labor migrants are facing many additional challenges due to COVID-19 and are unlikely to be able to access adequate information, assistance or health services. With many businesses closing down and construction works halting due to the economic impact of the pandemic and the loss in oil revenues, these labor migrants are now facing unemployment and a subsequent loss of income and the right of residence. Along with the worldwide closure of borders, migrant workers became stranded, were unable to find new employment or to return home, prompting some states to even evacuate their citizens from the region.

Migrant workers who did not lose their employment are equally becoming more vulnerable due to the pandemic. Temporary labor migrants are often employed in essential sectors, such as food production, cleaning and health care. This however, puts the workers at a high risk of getting infected with the novel Coronavirus. Additionally, living conditions for temporary migrant workers are often poorly and overcrowded, further increasing the risk of infection. Domestic workers living with their employer on the other hand might be increasingly isolated due to lockdowns, putting them at a heightened risk of abuse and sexual harassment.

Remittances

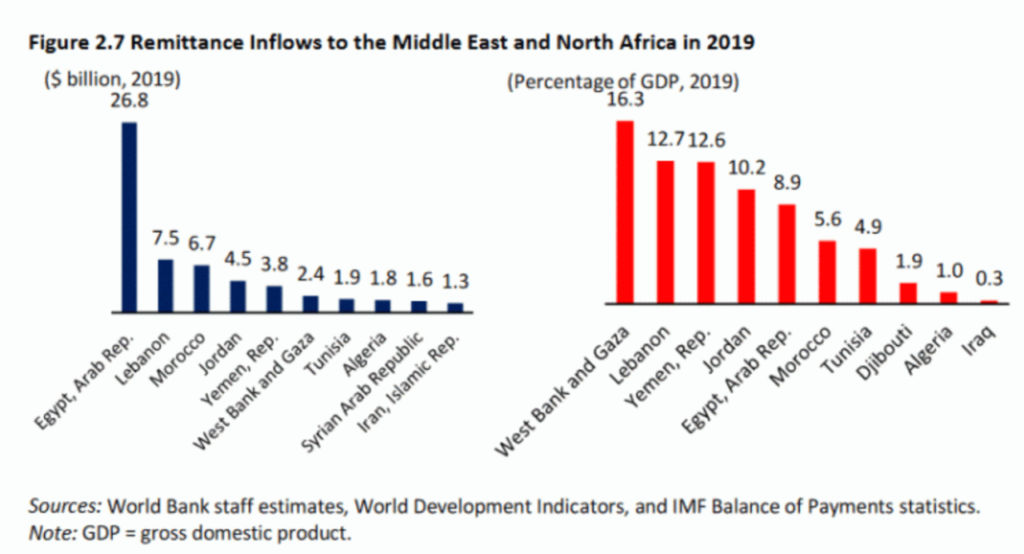

Corresponding to migration numbers, the region is receiving a considerable amount of remittances annually. In 2019, countries of the Middle East received a total of 54 billion US$ in remittances, of which 34.4 billion US$ came from other countries within the region. Remittances constitute a considerable share of the GDP of some countries, notably Palestine, Lebanon and Yemen, making remittances inflows crucial to the local economy. However, loss of employment also halted migrant remittances, on which not only these countries’ economies rely but also many families. The World Bank estimates, that due to the effect of the pandem

ic on global markets, travel bans, the disruption of internal trade, and a fall in the price of oil, the remittance flow to the MENA region will decrease by approximately 20%.

Conclusion

With COVID-19 infections still on the rise, the Middle East is struggling to contain the pandemic, prevent economic collapse, and protect its citizens, while many states were already facing economic hardship, conflict and turmoil. The pandemic highlights once again the vulnerability of refugees, internally displaced and labor migrants in the Middle East and the need to protect and support migrants, who play an essential role within the region.

About the Author

Michaela Balluff joined Trust as a Junior Officer for the Research and Third Party Monitoring Department. She holds a Master’s Degree in Middle Eastern Studies from Germany and Lebanon and previously worked in Lebanon, Jordan and Ghana with a focus on issues related to displacement, migration and employability.

Learn more about Michaela on LinkedIn.

Sources

GhanaWeb (2020, June 22nd), 200 Ghanaian domestic workers in Lebanon evacuated to Ghana. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/200-Ghanaian-domestic-workers-in-Lebanon-evacuated-to-Ghana-986155.

GhanaWeb (2020, June 6th), Stranded Ghanaians in every part of the world will be evacuated – Foreign Affairs Minister. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/NewsArchive/Stranded-Ghanaians-in-every-part-of-the-world-will-be-evacuated-Foreign-Affairs-Minister-972184.

International Labour Organization (2020), COVID-19: Labour Market Impact and Policy Response in the Arab States. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—arabstates/—ro-beirut/documents/briefingnote/wcms_744832.pdf.

International Labour Organization (2020), Impact of COVID-19 on Syrian refugees and host communities in Jordan and Lebanon. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/—arabstates/—ro-beirut/documents/briefingnote/wcms_749356.pdf.

International Labour Organization, Labour Migration in the Arab States. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://www.ilo.org/beirut/areasofwork/labour-migration/WCMS_514910/lang–en/index.htm.

International Organization for Migration (2020, October 5th), Travel Restrictions Related to Travel Routes. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://migration.iom.int/.

The World Bank (2020), Migration and Remittances, Annual Remittances Data. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/labormarkets/brief/migration-and-remittances.

The World Bank (2020), COVID-19 Crisis Through a Migration Lens, in: Migration and Development Brief No. 3. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/989721587512418006/COVID-19-Crisis-Through-a-Migration-Lens.

United Nations (2020), Policy Brief: COVID-19 and People on the Move. https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/sg_policy_brief_on_people_on_the_move.pdf.

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Population Division (2019), International Migration Stock 2019 by Origin and Destination. Accessed October 5th 2020. https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/migration/data/estimates2/estimates19.asp.

United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia (2020), Situation Report on International Migration 2019. The Global Compact for Safe, Orderly and Regular Migration in the Context of the Arab Region. https://rocairo.iom.int/sites/default/files/publication/situation-report-international-migration-2019-english_0_0.pdf.

United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (2020), Global Trends. Forced Displacement in 2019. https://www.unhcr.org/5ee200e37.pdf.

World Health Organization (2020, October 8th), WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard. Accessed October 8th 2020. https://covid19.who.int/.